The Ugly Truth of Corrosion, Drinking Water and Health Risk

Corrosion, Drinking Water and Health

Testing for Corrosivity of Your Water Supplies

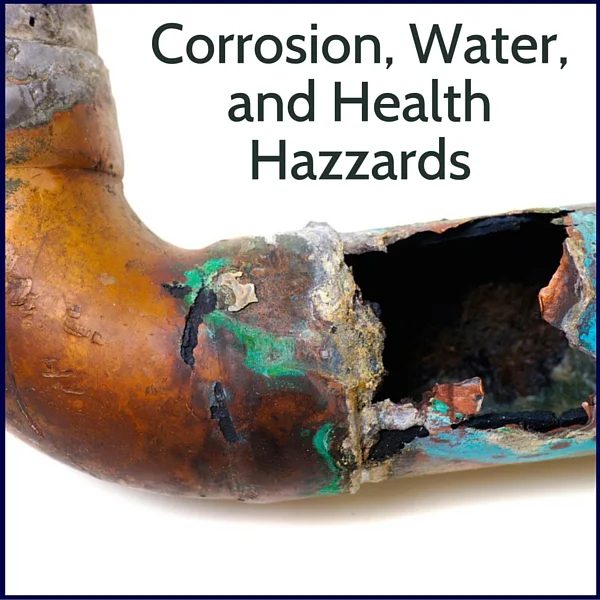

Corrosive water is a condition where the water quality dissolves metals from the metallic plumbing it flows through at an excessive rate. Corrosivity is caused by low pH values, low alkalinity, a higher specific conductivity and a higher temperature of water.

Most surface and some ground waters in New England are highly corrosive. Some signs that your water is corrosive include a blue-green stain at drip points in sinks and tubs. But just because you don’t see staining doesn’t mean your water isn’t corrosive. Lead does not stain or flavor the water, so the presence of this toxic metal in your water may go unnoticed. While checking your home plumbing for lead pipes is a good start, remember copper piping installed before the 1980s used lead solder in the joints, which could also present a health risk.

Corrosivity can also cause physical damage to piping, which may leach led into your drinking water and hasten the need to replace your plumbing. Copper gives water a metallic taste, and can stain clothing and hair. Flushing the pipes will lessen the metallic taste, but won’t prevent damage to your pipes.

Testing Your Water

Before sending a sample off to the lab, take a look at your home plumbing. Was your house built before 1980? If so, do you know what material your plumbing is made of? If there are copper pipes or pipe fittings, tests should be done to measure levels of copper, lead and other metals in your water. Also, consider pumps and fitting coming into your home. If there is more than one type of pipe, find which pipes serve the faucets most used for drinking. If both hot and cold water flows through PVC plastic pipes, there is little to no health risk other than lead from faucets or well pumps.

The best way to test your water for corrosivity is to follow the EPA’s sampling guidelines. Samples must be taken after the water has been left stagnant in your pipes for at least the previous six hours, such as first thing in the morning. The 1-liter sample should be taken at the faucet most used for drinking.

A key test for determining corrosivity is pH. If the pH is 6 or below, that is highly corrosive, and treatment will likely be needed. If the pH is 6 through 6.9, the water is somewhat corrosive, and more testing may be necessary. Higher pH values mean the water is likely not corrosive, but further testing may be warranted, depending on the case.

Ways to Reduce Health Risks for Corrosive Water

Flushing pipes is a common way for homeowners to mitigate the health risks caused by corrosive water. Metals build up in water as it sits stagnant in the plumbing system. This is most common from 11 p.m. to 6 a.m., when people are sleeping, and between 8 a.m. and four p.m., when the family is usually at school or work. Using stagnant water for drinking, making coffee or frozen fruit juices can result in excessive lead or copper intake.

Flush until the water from the faucet has turned cold, or about a minute. This indicates fresh water from your well, or outside source is now flowing into the home.

Also, use cold water when making coffee or cooking, as hot water can contain more metals. Consider using drinking water from a trusted outside source, such as bottled water.

Treatments for Corrosivity

There are some methods, both low cost and expensive, that can be utilized to neutralize water. Adding calcite chips to the bottom of the existing dug well can reduce corrosivity at a low cost, but can also cause hardness and alter the water’s taste. This is recommended only with the guidance of a water quality expert, as there are many details to consider before moving forward.

A more high-tech approach is diluting a solution of soda ash or baking soda into the water using a chemical feed pump. This does not increase hardness, and the solution can be altered depending on the water. It could, however, cause damage to some mechanical devices, requires routine inspections and filling of the chemical solution every few weeks.

For more information about corrosivity, contact the DES Drinking Water and Groundwater Bureau or consult a water technician for inspection and testing information. For further information on how to solve the corrosion problem, download our service brochure.